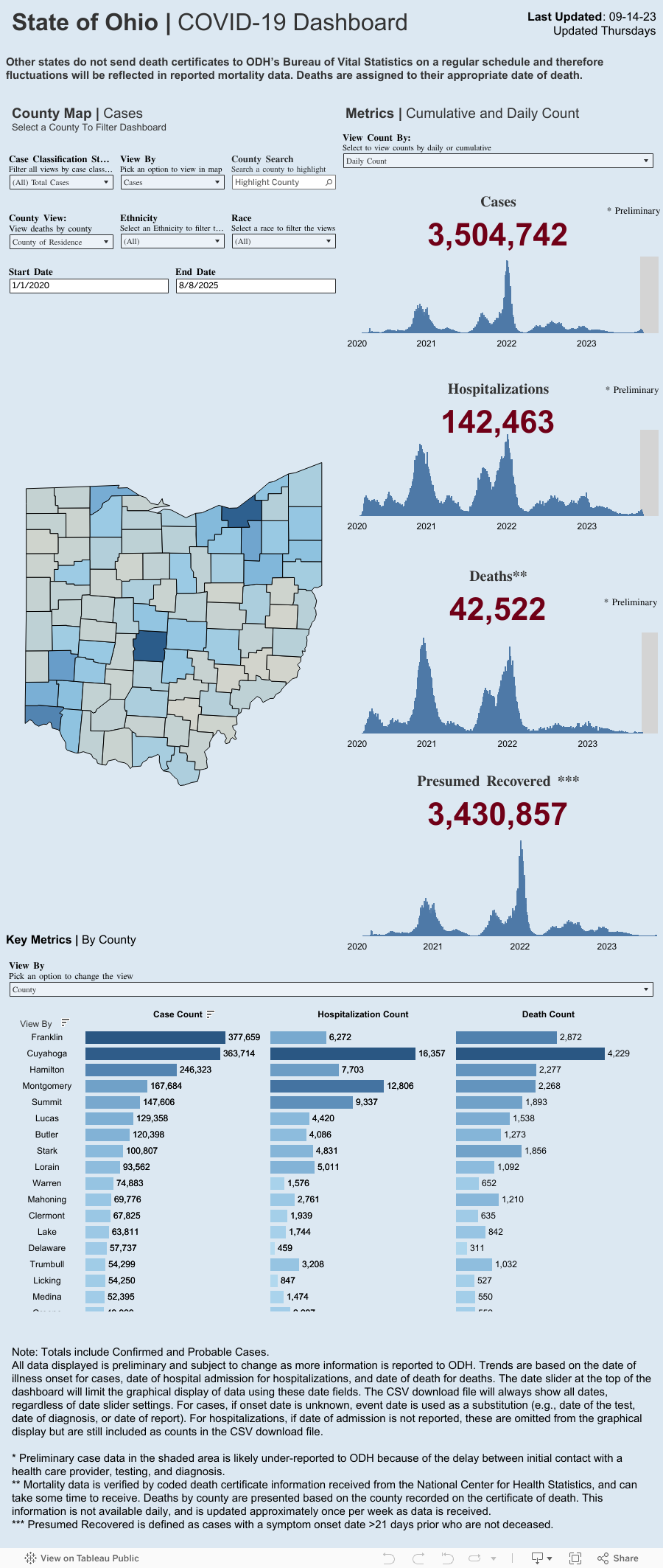

The Ohio Department of Health gets daily updates on the total number of beds and ventilators that could be available for COVID-19 patients at hospitals throughout the state. But so far the agency hasn’t provided any hospital-by-hospital breakdown, and the agencies that collect capacity information on their behalf have also declined to release their assessments.

The result: Ohioans don’t know how many beds and respirators are available where they live. Timely and meaningful knowledge could benefit Ohioans from a health perspective, while also helping them understand the range of public policy issues surrounding the crisis.

The availability of resources to care for COVID-19 patients could mean life or death for thousands of Ohioans.

“It’s what keeps me awake at night,” said Ohio Department of Health (ODH) director of health Amy Acton, MD, MPH of her fear of running out of beds, ventilators and personal protective equipment. Governor Mike DeWine echoed “that is what we really fear” at the same Ohio Statehouse Press Conference on March 25.

DeWine has received national recognition for the aggressive actions he’s taken to protect the state of Ohio. He and Dr. Acton report numbers, and announce action items daily at 2:00 p.m. Estimates from Ohio State University and the Cleveland Clinic project that at Ohio’s rate of new COVID-19 patients, the state may have 6,000 or as many as 10,000 a day by late April.

“[A]t the projected peak, we need to go up 3x in our hospital capacity,” DeWine tweeted on March 27. “We have a long way to go.”

However, neither he nor the department of health has stated where the greatest needs are on a local basis. Nor has baseline information for different areas been made available.

At first, ODH spokesperson Melanie Amato told Eye on Ohio that the department only gets the aggregate numbers for beds and equipment from the Ohio Hospital Association and that any detailed information would have to come from that organization.

The association’s spokesperson, John Palmer, declined to release the numbers that they share daily with ODH.

ODH also tracks beds through Surgenet, administered by the Greater Dayton Area Health Information Network.

“We’re not actually reporting any bed data or any of the specifics that we’re tracking with Surgenet publicly,” said Sarah Hackenbracht, president and CEO of the Greater Dayton Hospital Association, calling the database an “internal management tool.”

“It’s not a public tracking tool for public reporting,” Hackenbracht said. And despite the data collection being done with federal and state funds, “it’s a tool that we own and manage through the hospital association. So it’s not owned by the Ohio Department of Health or any other entity.”

In a state with nearly 45,000 square miles, that local information could tell citizens more about Ohio’s readiness to deal with emergencies for all its residents. Availability of beds and respirators in Cincinnati, for example, would mean little if hot spots of emergencies were concentrated in Ashtabula, nearly 300 miles away by car.

Efforts to get the data independently also met with roadblocks.

Eye on Ohio contacted 30 hospitals around Ohio, asking for their bed and ventilator numbers, as well as any particular notes or requests from each hospital. Only two reported their bed numbers. Several hospitals noted that they share this information daily with health departments and recommended contacting the ODH for aggregate numbers.

Marlene Harris-Taylor, health reporter for Ideastream.org, reported similar difficulties. Although she was able to obtain a system-wide ventilator count as of March 17, she noted, “Summa Health System in Akron would not share the numbers with me, they just did not want to talk about it.”

Michael Bernstein, System Director of Corporate Communications and Public Relations of Summa Health System in Akron said that giving out daily updates of capacity numbers to the public was unreasonable, even though those numbers are reported daily to the local and state health departments.

“I think the overall feeling is that giving specific numbers will only cause confusion. That the numbers change drastically and quickly. If we give numbers at 3:00 those will change by 3:30 making reported information inaccurate,” he said.

“Hospitals are communicating and collaborating to get patients the best care possible and can direct resources accordingly,” Bernstein said. “Bed and ventilator numbers of an individual hospital should not direct the patient’s decision of where to receive care.”

Promoting public health

Information about local hospitals’ beds and ventilator availability changes on a day-to-day basis, so Eye on Ohio’s goal is to provide local numbers in a way that could be updated daily, along with hospital requests.

Local hospitals’ requests and notes could be “really useful,” said Rupali Limaye, an expert in public health communication at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “People are wanting to know what they can do to help.” That might include requests for supplies, volunteers, or other things.

She was less certain about how specific numbers for beds and ventilators would translate into action items from a public health perspective. “Notoriously, as humans, we’re really terrible about estimating risk,” Limaye said. She worried that plain numbers might create fear, or lead to complacency.

However, when it comes to the coronavirus epidemic, many people already feel anxious, said Lise Van Susteren. She’s a general and forensic psychiatrist in the Washington, D.C. area who has studied the impacts of generalized anxiety for another major social problem — climate change. As she sees it, up-to-date information about local hospitals’ beds and equipment could help reduce some of that anxiety.

“One of the major components of anxiety is uncertainty,” Van Susteren said. Specific information that someone can understand in the context of his or her situation can reduce that uncertainty. That’s true even if the news “may not be something you want to hear.”

“When you replace uncertainty with knowledge, there is an immense sense of relief,” she explained. From a mental health perspective, someone can then better process feelings of anxiety, fear or other emotions.

“We can go from that uncertainty to unpacking the elements of the threat — and unpacking them in terms of what’s emotional, what’s rational, what’s hard data,” Van Susteren said. “And something else, then we can order in our minds where the work has to be done.”

Along those lines, specific knowledge helps “reframe the social isolation and the feeling of impotence” that many people might feel as a result of the epidemic. Instead of viewing public health measures as restrictions on personal liberties, information can help “reframe that as an empowering action that we can all do collectively,” Van Susteren added. “This is where the light is: It’s when we’re all working collectively in this.”

Informing public discussions

The information also matters for advancing public understanding and discussion of policy issues, said Catherine Turcer, executive director of Common Cause Ohio. In her view, the need for localized information about hospital resources is akin to other situations in which members of the voting public need information.

“The goal really is for the information to be meaningful,” Turcer said. In other words, “we need to make sense of the information.” Too often, however, information is disclosed in ways so “you can’t actually figure out what it means.”

“The next part, that’s almost more important, is for it [the information] to be timely,” she added. So, even when citizens eventually get requested information, it may come “just a little too late” to make a difference.

Other examples where the problem crops up include government budgeting matters and campaign finance disclosures. When it comes to voting, for example, some of Ohio’s boards of elections report separately on how many people vote early in person and how many vote by mail. Others just report the total numbers lumped together. “For us to understand what works and what appeals to voters, it’s really helpful to have that information segregated,” Turcer said.

The COVID-19 epidemic isn’t taking place in a political vacuum either.

“The thing is: Democracy doesn’t stop just because there’s a pandemic. We have an election that’s going on,” Turcer notes. “And if ‘we the people’ has meaning, that means we need information from government so that we can identify problems and possibly solutions, and so we can also identify corruption, and then come up with possible solutions.”

“We are in a weird age of misinformation, and of people providing talking points that are not completely accurate. And we need to make sure that we have as much good information as possible,” Turcer added.

“That’s why…it’s so important to have that source material, so we can all together figure out what’s real,” she said. Source material can let disinterested parties verify aggregate numbers, for example. Or, it can identify where shortages may be especially acute.

“When we go back to the source material, then we have the ability to actually have a conversation about facts,” Turcer said.

“Every single specific case of not getting information highlights how this is a systemic problem,” she said.

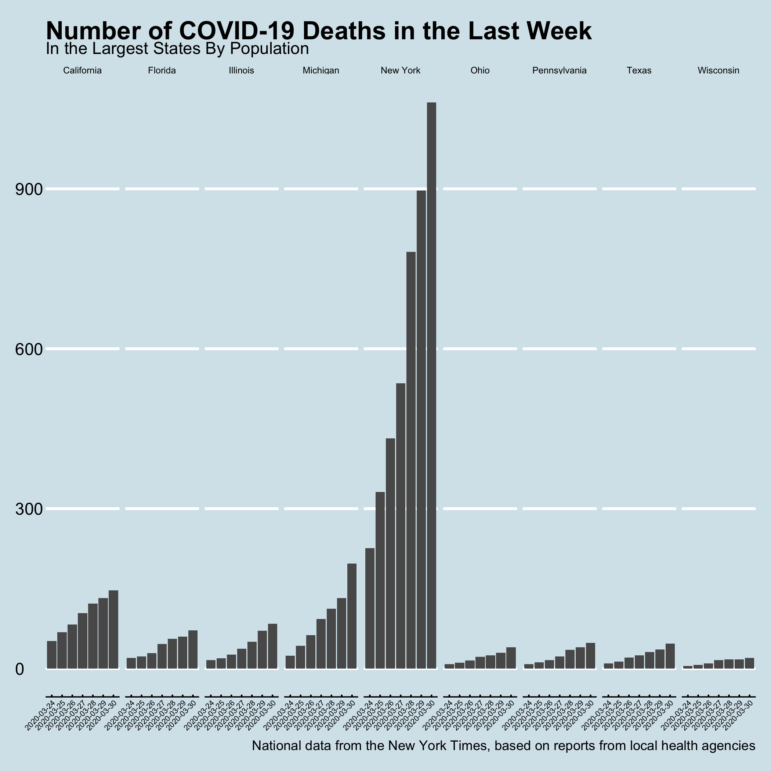

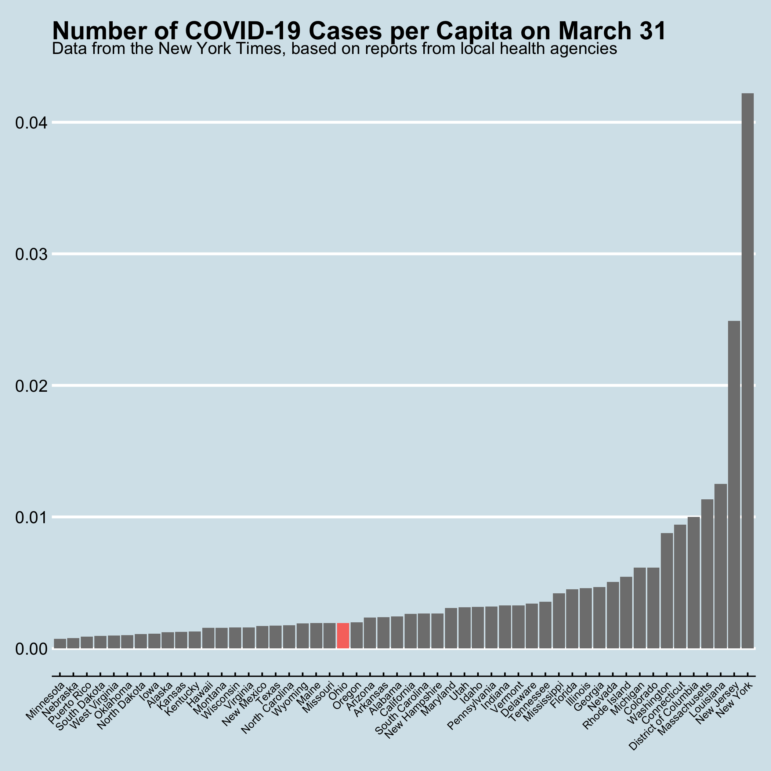

Data for graphs in this article comes from the New York Times, based on reports from state and local health agencies. This specific information is available for republishing.

This article first appeared on Eye on Ohio and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.